A reflection on what it means to mother, to grieve, to fish, and to feel death not as absence but as sacred presence.

I never thought motherhood would find me. Not in the way people imagine with cribs and lullabies and baby showers. But it showed up in my body and in the way I loved. It showed up in how I listened. In how I held grief like it was something small and breathing. I’ve been the one to feed others when I was hungry. I’ve learned the shape of safety by being the one who builds it. I’ve wiped tears from the faces of people who didn’t know how to say thank you and still I stayed. I’ve looked at the world with the kind of softness that gets mistaken for weakness but is anything but. That softness has teeth when it needs to.

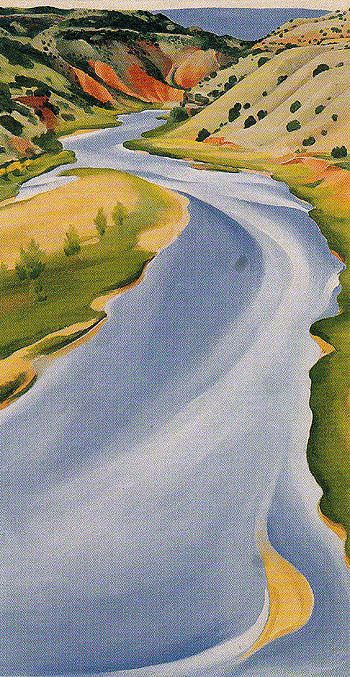

That evening was like any other. Quiet. I needed the water more than I needed answers. I didn’t plan to catch anything important. Just wanted stillness. The kind of stillness that teaches you how to breathe again. The river was slow and shining and I felt myself return to something old. Something wordless. When the line tugged it felt different. Like being chosen. I reeled her in slowly. She wasn’t thrashing. Just weight and breath and river muscle. When I lifted her from the water I felt it right away. Something in me stirred. I could feel her body before I even really saw her. I knew she was a mother. I don’t know how I knew. I just did.

She was thick with life. Her belly was full in a way that made my hands tremble. I didn’t want to touch her there. I didn’t want to disturb what she carried. I could feel it without pressure. Her ovaries held something ancient and sacred and I felt like I was intruding. There was awe in that moment. And fear. Not of her but of what it meant to be holding her. I’ve been that full before. With hope. With pain. With things I couldn’t name but still carried.

I took her home. I didn’t want to kill her. Not in the cruel way. But I knew the story had already started. I had already stepped into it. My wife stood on the porch, the light catching her hair, silent like she always is when something holy is happening. I laid the fish down gently. I met her eyes and there was nothing there but I felt seen. I held the blade for a long time before I moved. When I finally did I went slow. Careful. And when I opened her belly the eggs spilled out like pearls and yolk and memory. So many. More than I could count. Bright and wet and unreal. It took my breath.

That’s what death feels like sometimes. Not violence or absence, but unbearable fullness. Like swinging too high and knowing you can’t take it back. Like saying goodbye but running out of time. Like holding your breath too long in silence that once felt safe. Death isn’t always loud. Sometimes it spills gently across a cutting board while your hands try to make sense of what they’ve done.

I stood there with my hands inside her and time stopped. I felt like I was reaching into the belly of the river itself. I didn’t cry but I think my soul did. I didn’t feel proud. I didn’t feel sorry. I felt everything. That fish would have eaten countless salmon and steelhead juveniles like it already had been doing for years. She would have taken futures into her mouth without pause. But she was still a mother. A giver. A taker. A piece of the whole. I had interrupted that. And yet I had honored it too.

My wife placed a hand on my back. It was the smallest touch but it steadied me. We finished gutting her together in silence. We kept the meat for crab bait. Let the eggs return to the earth. I whispered something I can’t remember now but I know it was true. I know it came from the part of me that understands sacrifice. The part that knows not all mothers give birth. Some of us just hold space. Some of us know life even when it slips through our hands.

That night I sat with the smell of river on my skin and thought about the way I knew. The way I could feel the life inside her before I ever cut her open. That wasn’t science. That was spirit. That was the thread that ties us to the water and the soil and the dark. That was the kind of knowing you don’t get from books or facts or names. It lives in your hands. It lives in the silence after. And it waits. It waits for those of us who are brave enough to feel it.

That was the day I caught a two and a half pound northern pikeminnow and met something divine. Not because I conquered her but because I saw her. Because I felt her. Because I recognized the weight of her body in a way I have only ever recognized my own. That was the day I understood that to mother is not just to birth. It is to bear witness. To take life and give it back. To know when to hold and when to let go. That was the day I learned I am more river than anything else.

You must be logged in to post a comment.